What would we expect from a company with more than 150,000 people in its R&D team?

Research and development (R&D). We speak of them as a couple walking hand in hand. Often with their offspring, innovation (R&D&I). But the discovery of new knowledge (science), the development of new products and tools (technology), and how these reach society (innovation), like any good family, have their differences and disagreements. Getting them to get along is a challenge.

The public debate on science, technology and innovation policy is largely dominated by the "pipeline" metaphor. According to this metaphor, new technological ideas emerge as a result of scientific discoveries and flow naturally through applied research, design, manufacturing, production, research and development. marketing and marketing.

The scientific knowledge of a society would be like the accumulated balance in an intellectual savings account. The ratio of R&D expenditures to GDP is used as a measure of the future and economic potential of regions and countries.

Spain is not particularly well portrayed by this index. But even so, in Spain we have some 150,000 researchers and a reasonable scientific output. The question arises as to what return we get from our stock of knowledge. Or as he explains this articleWhat would we expect from a company with more than 150,000 people in its R&D team?

The answer is that Spain (like Europe) has difficulties in transforming knowledge into applications. To understand why, it is necessary to enter the pipeline and observe how technology transfer occurs. The reality is more complex than the linear model. Internet pioneer Bob Metcalfe already said that "invention is a flower, innovation is a weed"..

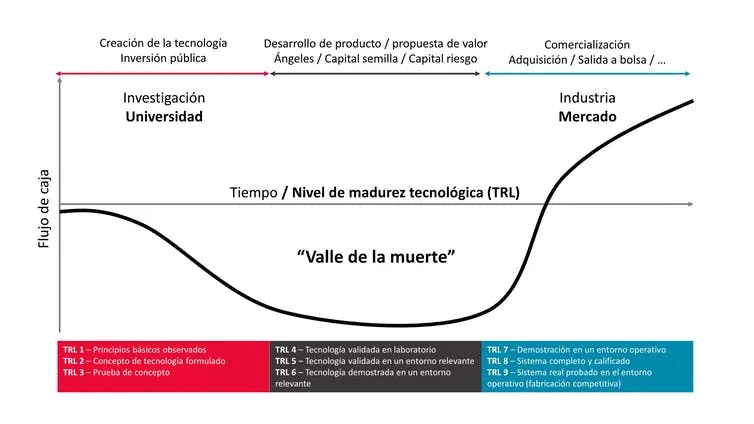

The level of maturity of a technology can be gauged by using the TRL maturity index (short for Technological Readiness Level) . Research tends to focus on technology development at levels 1 to 3. Commercialisation requires a proven prototype in a relevant environment, robust and with a maintenance operation at level 6, 7 or higher. Maturation is often slower and more costly than expected. In fact, the metaphor most often used to describe this transfer process is that of the "valley of death".

Technological maturation and the 'Valley of Death'.

Crossing this valley requires players with a wide range of skills: technical, commercial, project management, property rights, recruitment, leadership, negotiation, as well as the financing to cover a prolonged negative cash flow.

Creating the conditions and incentives for the effective collaboration of these actors is the challenge facing innovation policy. Everyone wants to create the next Silicon Valley. Few get the formula right. The process, however, has been studied extensively since the 1970s and there are common patterns that can and should serve as a reference. We will highlight three:

-Ownership of industrial property rights and regulatory and organisational and management flexibility.

-Incentives for recruitment and mobility of people and resources.

-Public and private funding.

In the US, the Morill Act of 1862, which instituted the transfer of public land to universities, turned them into laboratories and innovation centres. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 gave universities ownership of publicly funded research results. The number of patents and transfer activity experienced an enormous boost. Technology transfer offices (TTOs) were set up to manage them.

In the resulting (not necessarily ideal) transfer model, the university collaborates with researchers to determine which results are viable, patent them and create a commercialisation strategy. Technology can be licensed directly to established companies, but with high-risk or disruptive technologies. Typically, companies are created (spin-off) by the researchers themselves.

The start-upunderstood as a temporary organisation whose mission is to finding and validating a scalable and repeatable business modelis the transfer instrument par excellence. Public capital usually finances the early stages of development, but private venture capital is the most important transfer instrument. element determinant.

Ideally, when the transfer is successful, the university earns income from the licences, closing a potential virtuous circle. The reality is that few technologies end up producing more than mediocre results, so the process requires long-term vision, sustained commitment and scale.

The MIT model versus the European divide

In the USA, MIT, established in 1861, is a benchmark for this transfer model. Stanford University has been for the revolution of the hardware and information in Silicon Valley. In the UK, Imperial Innovations was created as a transfer department of Imperial College in 1986. It subsequently became a subsidiary and in 2006 its shares were admitted to trading on the London Alternative Market. In the same year Cambridge Enterprise as a transfer unit of the University of Cambridge.

Outside the Anglo-Saxon sphere, some European universities have started to follow the UK experience. Surprisingly, Germany, with a big push and strong support from regional administrations. The Technical University of Munich defines itself as "the entrepreneurial university", with initiatives such as the creation of the company UnternehmerTUM and the TUM Venture Labs.

In Spain, both the Science, Technology and Innovation Act as the Law on Universities incorporate the essential ingredients. But beyond legality, there are social and cultural factors, such as risk aversion and receptiveness to new designsand tacit knowledge that is not directly replicable.

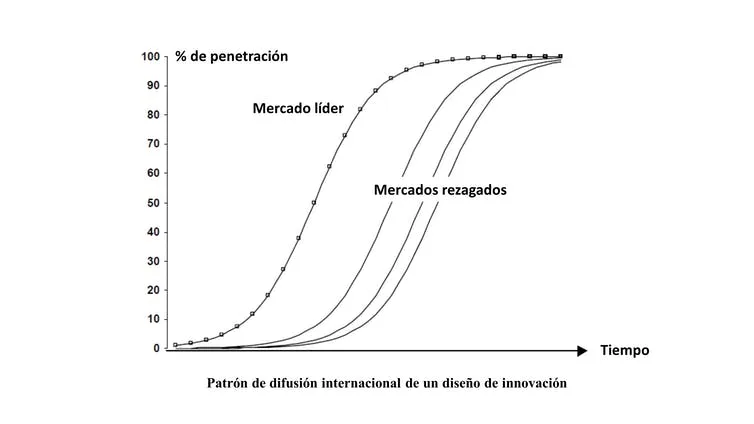

Pattern of international diffusion of an innovation design

Europe is aware of the productivity gap in its innovation model. Not only with the US, but also with countries like Israel, Singapore and South Korea with similar models. And of course with China, with a different model. The European Commission has been emphasising the need to adopt these practices for years. Improving technology transfer and cooperation between companies, research centres and universities is one of its priorities for 2021 - 2027.

The evolution that the financial industry is undergoing with the advance of participatory finance platforms (equity crowdfunding), decentralisation and the hoped-for tokenisation will offer alternative or complementary avenues of financing, and will increase competition and pressure on transfer models.

The government of Spain has just published in February 2021 the Spain Entrepreneurial Nation Strategyin which three levers are identified: education, R&D&I and innovative entrepreneurship. Spain cannot be left behind, it is said. But Spain already is. Catching up with its European and international peers is not a matter of voluntarism.

We believe it is fundamentally a question of intelligence and humility. Intelligence to understand and learn from best practices. Humility to adopt and assimilate them by doing, as the current Italian president would say, whatever it takes.